| March 6 - 10, 2024 | ARTMADRID’24, Stand 4, Galería Luisa Pita |

| February 3 - March 3, 2024 | PANGÄA, solo exhibition, offspace Milchstrasse 4, Munich, Germany. |

| Januar 19 - Februar 29, 2024 | PODER INTERIOR, Galería Luisa Pita, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Artists: Menchu Lamas, Rut Massó, Ana Margarita Ramírez. |

| October 13 - 25, 2023 | GLÜCK OHNE ENDE, PING RODACH contemporary, Munich, Germany. Artists: Katharina Andress, Tim Bennett, David Borgmann, Nena Čermák, Leonhard Hurzlmeier, Rut Massó, Viola Relle, Melanie Siegel, Martin Spengler, Olga Wiedenhöft, Martin Wöhrl. |

| October 20 – 23, 2023 | EDEN, Munich, Germany. Curated by Judith Grassl. Artists: Judith Grassl, Analía Martínez, Rut Massó, Samaya Almas Thier, Elina Uschbalis. |

| May 5 - 14, 2023 | GESOTTEN, Galerie FOE, Munich, Germany. Artists: Vincent Kern, Analía Martínez, Rut Massó, Tom Schulhauser, Eunji Seo, Alix Stadtbäumer, Lorenz Straßl, Elina Uschbalis, Adrian Wald. |

| July 14 - 30, 2023 | FLORA UND FAUNA, offspace P38, Munich, Germany. Curated by Rut Massó and Analía Martínez. Artists: Judith Grassl, Analía Martínez, Rut Massó, Viola Relle, Anne Rößner, Alix Stadtbäumer, Stefanie Ullmann, Elina Uschbalis, Sharon Wagner. |

| 2022 | ENTWEDER JETZT ODER SPÄTER, Kösk Munich, Germany. Curated by Emanuel Wadé and Sebastian Mayrhofer. |

| October 14 - 16, 2022 | ALLES FÜR ALLE, OpenQ artspace, Munich, Germany. Curated by Florian Haller. |

| December 02, 2022 - February 28, 2023 | ON THE ROCKS, solo exhibition, P38, Munich, Germany. |

| 1970 | Born in Vigo, Spain |

| 1990 - 1995 | Graduate, Painting, Academy of Fine Arts Pontevedra, Universidad de Vigo, Spain |

| 1992 | First European Exchange Fellowship, Kingston University, London |

| 1997 - 1998 | Caixa-Galicia Foundation Fellowship, Academy of Fine Arts Munich, Germany |

| 1998 - 2004 | Diplom, Painting, Prof. Oehlen, Academy of Fine Arts Munich, Germany |

Tobias Teutenberg EN

Text of the catalog for the exhibition 13,6 MILLIARDEN JAHRE DANACH in CAS, Munich 2017-18.

Author: Tobias Teutenberg

Translation: Peter Adam

Depicting the Pre-Pictorial

Those who wish to approach the art of Rut Massó have a long way to go: according to the title of the show, it’s about 13.6 billion years after the Big Bang – a leap in time of 200 million years from the present into the past. This is the final phase of the Paleozoic, referred to in historical geology as the Permian period. The earliest traces of man will be left only 190 million years later. The Permian had no room for the development of complex life. From a biological perspective, it was rather a decay period sui generis, in which radical climatic changes led to a mass extinction that was unique in geological history: Up to 90% of the flora and fauna of the previous Carboniferous period fell victim to it. And yet we should not vilify the Permian as a pure degenerative age. From a geological point of view, there has hardly been a more creative time, as there were massive lithospheric changes in the Permian: Due to the collision of the major continents Laurussia and Gondwana, the entire land mass of the earth was united for the last time to a supercontinent, which covered 138 million km ². „Pangea“ (Whole Earth) – this is how the earliest theorist of geoscience Alfred Wegener, christened this gigantic formation in 1920. At its seam, a mountain range of eight kilometer in height piled up, on its shores, mega-monsoons regularly led to enormous erosions – today, however, hardly traces remain.

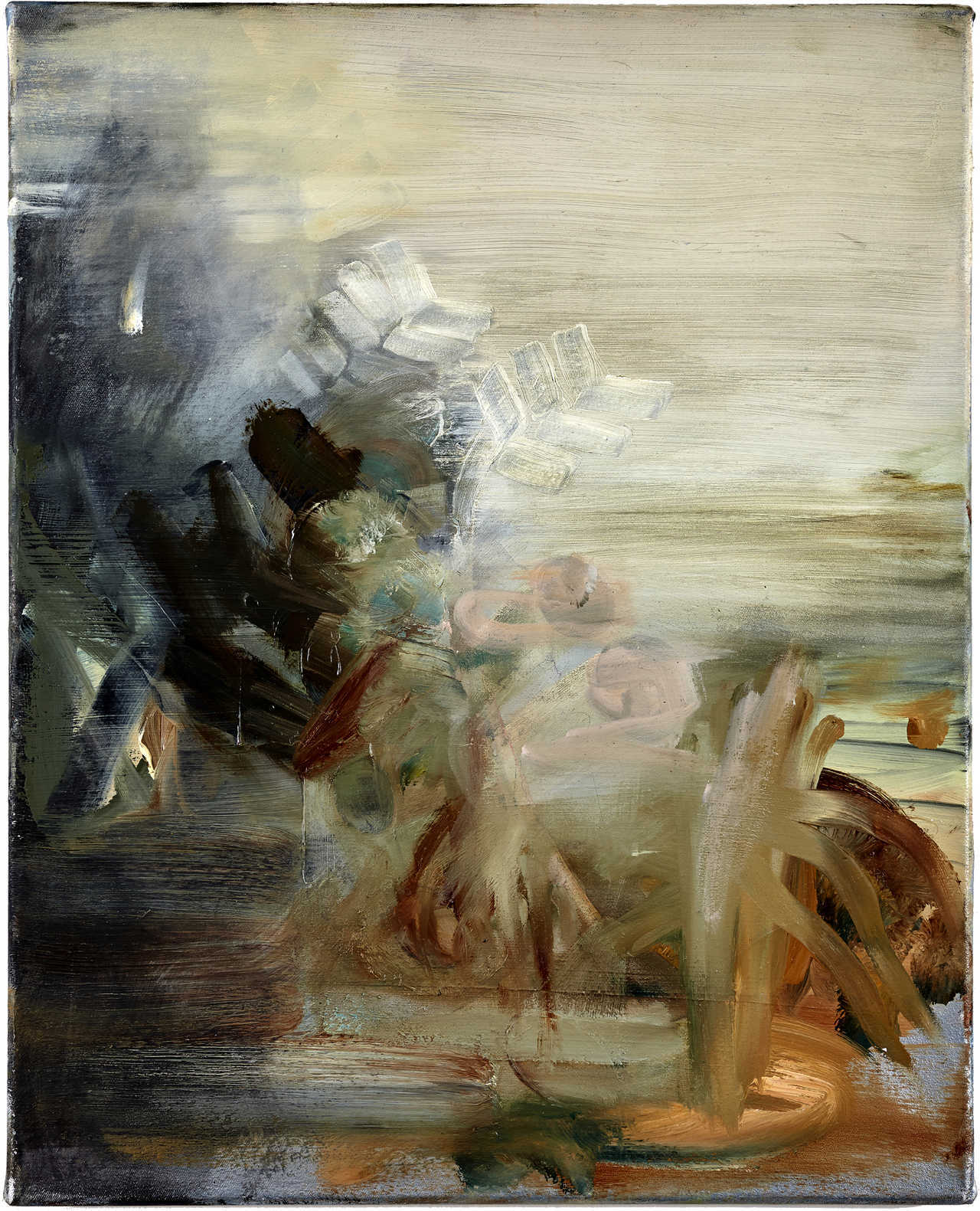

Rut Massó is fascinated by such naturally autonomous and at the same time inaccessible and distant form processes. These allow her to design free from indexical or iconographic restrictions and develop her own images with the help of autocreative methods. In her Œuvre, the Galician painter, draftswoman and photographer frequently refers to corresponding pre-historical as well as pre-figurative events: for example, in her large-scale visions of the Big Bang, which she presents as the propagation of light rays before the indefinite void of dark pictorial spaces, or on the emergence of Pangea at the moment of thecollision of huge tectonic plates.

Born 1970 in Vigo, Rut Massó studied painting at the Facultad de Bellas Artes de Pontevedra from 1990-1995. Very soon she received a number prestigious awards, such as the Prize for painting at the University of Vigo (1993) or the award of the Foundation Gregorio Prieto in Madrid (2000). A First European Exchange Fellowship took her to the Kingston Academy in London in 1992 for one year. In 1997 she was awarded a scholarship from the Caixa-Galicia Foundation to the Akademie der Bildenden Künste München, where she graduated in 2004 under the supervision of Markus Oehlen. To this day, Rut Massó has been able to present her work in nine solo exhibitions: the first in 1997 at the Galería Abel Lepina in Vigo, the last to date with Knust x Kunz + in Munich in 2014.

These biographical details do not appear here for the sake of form alone. Above all, they should make it clear that Rut Massó can already look back on a long-standing, dense and multifaceted Œuvre. So, it is quite remarkable that the artist resisted the obvious temptation to direct her exhibition in the CAS with a retrospectively view. On the contrary, what she offers are insights into current artistic interests and problems – a considerable number of pictures have even been created specifically for this show.

If one tries to approach their concerns conceptually and to highlight connecting factors between individual groups of works, then Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego, professor of aesthetics and art theory of the University of Vigo, gives an important hint. De Samaniego noted in his text for the Massó’s Vanitas exhibition in the Galería Artificial of Madrid in 2008: „It is clear that Rut Massó’s images respond more than anything to a fantastic power. Here, fantasy certainly predominates over any structure of the real or of facts“. Indeed, Massó keeps in her pictures a distance to the reference system of visible reality. Celestial beings, mythical Titans, prehistoric humans, cosmic constellations and fantastic forests are but a few of their favorite motives. And even the paintings she has portrayed as portraits do not refer to concrete persons, but once again give Massó’s pleasure in the figuration of the formless.

Stylistically, her paintings are emphatically painted, not infrequently provided with expressive, dynamic and broad brushstrokes. Although their color is sometimes strong, excessive contrasts or even garish elements are avoided. Precisely because of this, they set themselves apart from the works of the New Wild Painters of the eighties and nineties and seek to link up with the old, masterfully worthy aura of icons of European painting history. Especially the light of the woods and portraits betrays Massó’s art historical education and her exact study of the paintings Goyas and de la Tours.

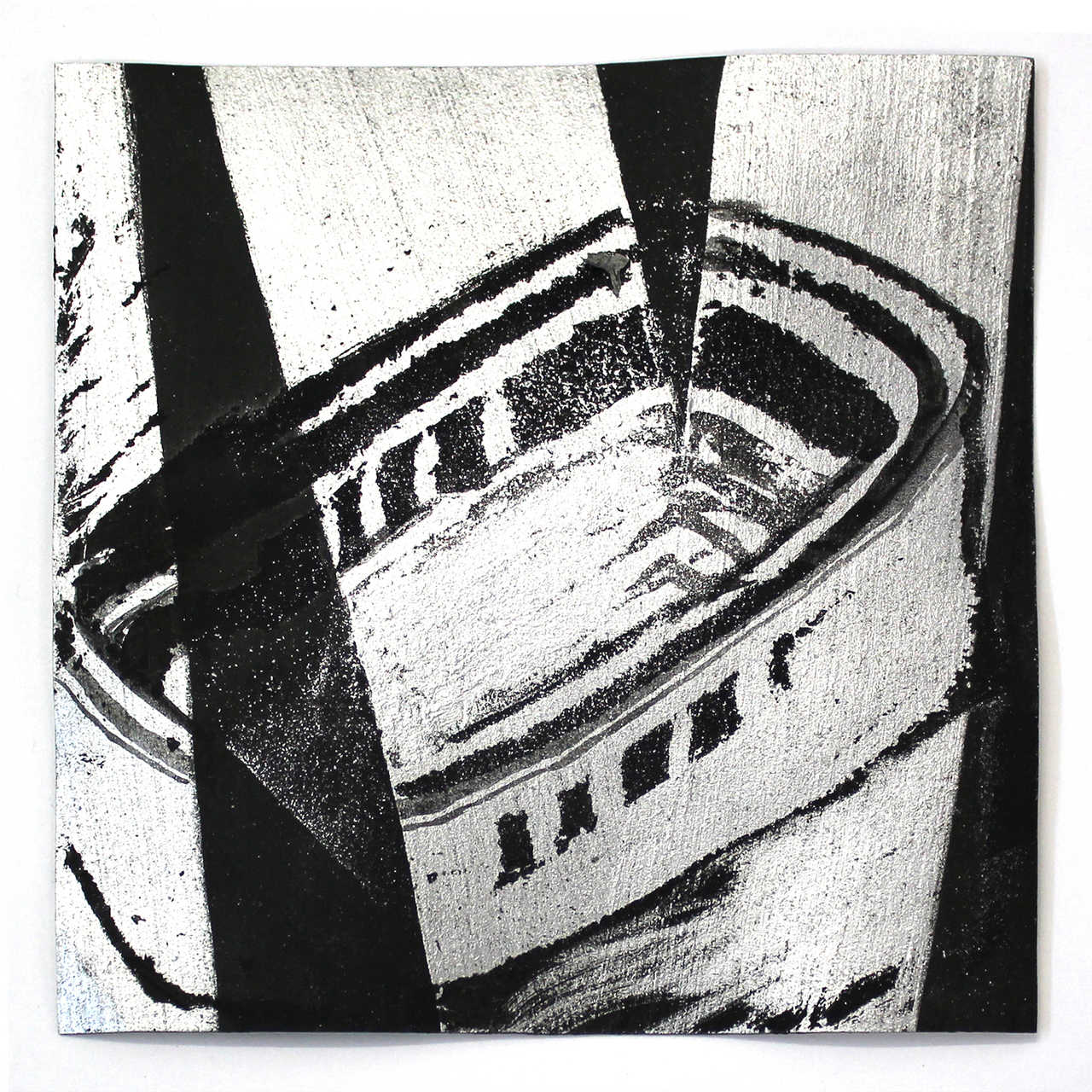

Nevertheless, it does fall to the beholder, not to fall into the fallacy, to recognize in the strongly gestural characteristics of the pictures primarily a strong need for self-expression, even self-reflection, because the factor “coincidence” is included systematically and at different levels in the process of image formation: We are talking about techniques of flushing up and rinsing underlaying paint layers, the partial scratching of hidden layers by the squeegee, the programmatic use of contaminated brushes when applying paint or even the application of aluminum paint, which produces completely different effects depending on the light situation. All these measures are taken by Massó to keep the process of design open to results – as did Marcel Duchamp and Guy Debord, who in the twentieth century created the random-integral component of artistic work. The influence of learned behavior patterns and established patterns of presentation is deliberately undermined by such procedures in favor of unexpected and ever-newer results. Consequently, at the beginning of every work Massó seldom has a theme or subject. Every picture gets its fair chance to mature unchecked before its designation. Even studio objects such as a drip tray or a cardboard screen for spray paint come to this right in Massó’s work and can evolve over time into random images of faces or forests.

Tobias Teutenberg DE

Text im Katalog der Ausstellung 13,6 MILLIARDEN JAHRE DANACH in CAS, München 2017-18.

Autor: Tobias Teutenberg

Vor-bildliches Verbildlichen

Wer sich der Kunst Rut Massós nähern möchte, hat einen weiten Weg vor sich: Gemäß dem Titel der Schau gilt es nämlich ganze 13,6 Milliarden Jahre nach dem Urknall anzusetzen – ein Zeitsprung von 200 Millionen Jahren von der Gegenwart in die Vergangenheit. Es ist dies die Endphase des Paläozoikums, die in der historischen Geologie als Perm-Periode bezeichnet wird. Die frühesten Spuren des Menschen werden erst 190 Millionen Jahre später hinterlassen werden. Das Perm bot der Entwicklung komplexen Lebens keinen Raum. Aus biologischer Perspektive war es vielmehr eine Verfallsperiode sui generis, in der radikale klimatische Veränderungen ein erdgeschichtlich einmaliges Massensterben mit sich brachten: Bis zu 90% der Flora und Fauna der vorausgegangenen Karbon-Zeit vielen ihm zum Opfer. Und doch wäre es zu kurz gegriffen, das Perm als reines Degenerationszeitalter zu schmähen. Aus geologischer Warte nämlich hat es kaum eine kreativere Zeit gegeben, ereigneten sich doch im Perm gewaltige lithosphärische Veränderungen: Durch die Kollision der Großkontinente Laurussia und Gondwana vereinte sich die gesamte Landmasse der Erde zum bisher letzten Mal zu einem Superkontinent, der 138 Millionen km² umfasste. „Pangaea“ (ganze Erde) – auf diesen Namen taufte ihr frühester Theoretiker, der Hamburger Geowissenschaftler, Alfred Wegener, diese gigantische Formation im Jahre 1920. An ihrer Schweißnaht türmte sich eine Gebirgskette von acht Kilometern Höhe auf, an ihren Küsten führten Mega-Monsune regelmäßig zu enormen Erosionen – heute jedoch ist von alledem mit bloßem Auge kaum noch etwas zu erkennen.

Rut Massó ist fasziniert von derart natürlich-autonomen und zugleich unzugänglich-distanzierten Formprozessen. Hier kann sie frei von indexikalischen oder ikonographischen Einschränkungen gestalten und mithilfe autokreativer Verfahren eigene Bilder entwickeln. In ihrem Œuvre nimmt die galizische Malerin, Zeichnerin und Fotografin daher immer wieder Bezug auf entsprechende vor-geschichtliche wie auch vor-bildliche Ereignisse: etwa in ihren großformatigen Visionen vom Big Bang, den sie als Ausbreitung von Lichtstrahlen vor dem unbestimmten Nichts dunkler Bildräume vorstellt, oder auf die Entstehung Pangaeas im Moment der Kollision riesiger tektonischer Platten.

1970 in Vigo geboren, studierte Rut Massó an der Facultad de Bellas Artes de Pontevedra von 1990 bis 1995 Malerei. Sehr bald schon erhielt sie eine Reihe renommierter Auszeichnungen, wie den Preis für Malerei der Universität Vigo (1993) oder den Drawing Prize der Stiftung Gregorio Prieto in Madrid (2000). Ein First European Exchange Fellowship führte sie 1992 für drei Monate an die Kingston Academy in Kingston upon Thames. 1997 gelangte sie dann mit einem Stipendium der Caixa-Galicia Stiftung an die Akademie der Bildenden Künste, wo sie 2004 ihr Diplom bei Markus Oehlen ablegte. Bis zum heutigen Tage konnte Rut Massó ihre Arbeiten im Rahmen von neun Einzelausstellungen präsentieren: die erste von ihnen 1997 in der Galerie Abel Lepina in Vigo, die bis dato letzte 2014 bei Knust x Kunz + in München.

Diese wenigen biographischen Angaben tauchen hier nicht allein der Form halber auf. Vor allem sollen sie verdeutlichen, dass Rut Massó bereits auf ein langjährig gewachsenes, dichtes und facettenreiches Œuvre zurückblicken kann. Es ist also durchaus bemerkenswert, dass die Künstlerin der naheliegenden Versuchung widerstand, ihre Ausstellung im CAS retrospektiv auszurichten. Was sie im Gegenteil anbietet, sind Einblicke in gegenwärtige künstlerische Interessen und Problemstellungen – nicht wenige Bilder sind gar eigens

für diese Schau entstanden.

Versucht man sich ihren Anliegen nun sprachlich zu nähern und verbindende Faktoren zwischen einzelnen Werkgruppen herauszustellen, so gibt Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego, Professor für Ästhetik und Kunsttheorie der Universität Vigo, einen wichtigen Fingerzeig. De Samaniego bemerkte in seinem Text zur Vanitas-Ausstellung Massós in der Madrilener Galería Artificial von 2008: „It is clear that Rut Massó’s images respond more than anything to a fantastic power. Here, fantasy certainly predominates over any structure of the real or of facts.“ In der Tat hält Massó in ihren Bildern Distanz zum Referenzsystem der sichtbaren Wirklichkeit. Himmlische Wesen, mythische Titanen, vorzeitliche Menschen, kosmische Konstellationen und phantastische Wälder sind nur einige ihrer bevorzugten Motive. Und selbst die von ihr als Porträts ausgewiesenen Malereien rekurrieren nicht auf konkrete Personen, sondern geben einmal mehr Massós Freude an der Figuration des Gestaltlosen Ausdruck.

Stilistisch sind ihre Bilder betont malerisch gehalten, nicht selten mit expressiven, dynamisch und breit aufgetragenen Pinselstrichen versehen. Ihre Farbigkeit ist zwar bisweilen kräftig, zu starke Kontraste oder gar grelle Elemente werden jedoch gemieden. Gerade dadurch setzen sie sich von Werken der Neuen Wilden aus den Achtziger- und Neunzigerjahren ab und suchen Anschluss an die altmeisterlich würdige Aura von Ikonen der europäischen Malereigeschichte. Insbesondere das Bildlicht der Wälder und Porträts verrät

Massós kunsthistorische Vorbildung und ihr genaues Studium der Gemälde Goyas und de la Tours.

Hüten sollte sich die Betrachterin, der Betrachter allerdings, ob des stark gestischen Duktus’ der Bilder dem Trugschluss zu verfallen, in ihnen sei in erster Linie ein starkes Bedürfnis nach Selbstdarstellung, gar Selbstbespiegelung zu erkennen. Systematisch und auf verschiedenen Ebenen wird nämlich der Faktor Zufall in den Prozess der Bildwerdung einbezogen: Die Rede ist von Techniken des Frei- und Hochspülens unterliegender Farbschichten, vom partiellen Aufkratzen verdeckter Layer durch die Rakel, von der programmatischen Verwendung verunreinigter Pinsel beim Farbauftrag oder auch von der Applikation von Aluminiumfarbe, die je nach Lichtsituation völlig unterschiedliche Effekte erzeugt. All diese Maßnahmen ergreift Massó, um den Prozess der Gestaltung ergebnisoffen zu halten –wie vor ihr schon Marcel Duchamp und Guy Debord, die im 20. Jahrhundert das Zufällige zum integralen Bestandteil künstlerischen Arbeitens erhoben. Der Einfluss erlernter Verhaltensweisen und eingeschliffener Darstellungsmuster wird durch solche Verfahren gezielt unterminiert, zugunsten unerwartbarer und immer neuer Resultate. Konsequenterweise steht am Beginn einer jeden Arbeit Massós selten ein Thema oder Sujet. Jedes Bild erhält vor seiner Bezeichnung die faire Chance, zu etwas Unvorhersehbarem heranzureifen. Selbst Ateliergegenstände wie eine Abtropfwanne oder eine Karton-Blende für Sprühfarbe kommen bei Massó zu diesem Recht

und können sich mit der Zeit zu Zufallsbildern von Gesichtern oder Wäldern entwickeln.

Noé Massó EN

Text of the catalog for the exhibition VANITAS in the GALERíA ARTIFICIAL, Madrid 2008.

Author: Noé Massó

Let there be light

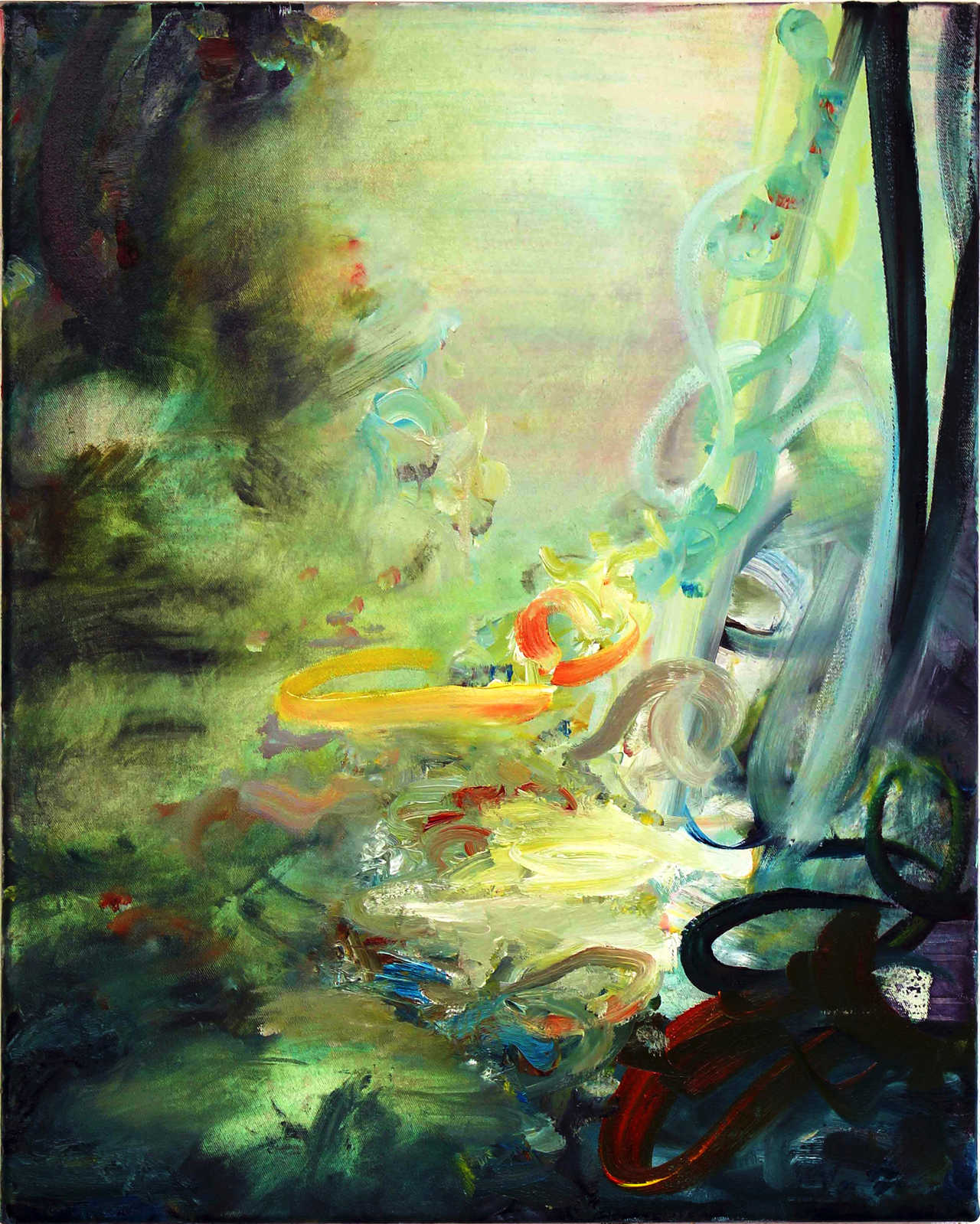

For some time Rut Massó has been exploring spaces —which are echoes— revealing hidden sub-worlds where things show aspects that the light hides. Now she leads us to the Forgotten Forest, by night, equipped with her candles.

The old dazzling gods howled “Let there be light!” and created shining universes with tops and bottoms, lefts and rights, with beginnings, ends and destinies, where the enlightened found sense. After centuries of creating Temples and Codes, Quoelet spoke to the Assembly: “There’s nothing new under the sun, everything is brief vain breeze, nothing benefits man.” Yesterday, after millennia of weaving constellations, Physics concluded: “Space is the echo of The Explosion that is now ending.” This revelation was so clear that it left us in a fog. Since then we feel our way in the dark, we splash around in the Black Tide. Where are we? What is this? Isn’t anyone going to light a candle?

On the Forgotten Forest someone —maybe an angel— has left a glove, some boots, a skull. Are these clues or false clues? Things forgotten or memories? We grope our way forward. Before us is a presence: witches, strangers jumping about, a night procession, everyone with his candle. The light, beside informing, also deforms. We’re playing with the mist.

On the Forgotten Mountain thieves are surprised to find abducted angels, dragged down by the light of Nothingness. Someone has lit a candle.

Noé Massó ES

Texto del catálogo de la exposición VANITAS en la GALERíA ARTIFICIAL, Madrid 2008.

Autor: Noé Massó

Hágase la luz

Rut Massó lleva mucho tiempo explorando espacios -que son ecos- desvelando submundos escondidos donde las cosas muestran aspectos que la luz oculta. Ahora nos conduce al Bosque del Olvido, a la hora de la noche, pertrechada con sus velas.

Los viejos dioses deslumbrantes bramaban “Hágase la luz!” y creaban universos fulgurantes con arriba y con abajo, con izquierda y con derecha, con principio, final y destino, donde los iluminados encontraban sentido. Tras siglos levantando Templos y Códigos, Quoelet habló en la Asamblea: “Nada hay nuevo bajo el sol, todo es brisa breve y vana, nada al hombre le aprovecha”. Ayer, tras milenios tejiendo constelaciones, concluyó la Física: “El espacio es el eco de La Explosión que ya se apaga”. Fue tan clara la revelación que nos dejó en tinieblas. Desde entonces palpamos en la oscuridad, chapoteamos en la Marea Negra. ¿Dónde estamos? ¿Qué es esto? ¿Nadie va a encender una candela?

En el Monte del Olvido alguien -tal vez un ángel- ha dejado un guante, unas botas, un cráneo ¿Son despistes o son pistas? ¿Son olvidos o recuerdos? Avanzamos a tientas. Ante nosotros una presencia: son figuras de aquelarre, extraňos dando sustos, una procesión nocturna, cada uno con su vela. La luz que informa, deforma. Jugamos a las tinieblas.

En el Monte del Olvido se sorprenden los ladrones: los ángeles arrebatados, arrastrados por la luz de la Nada. Alguien ha encendido una vela.

Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego EN

Text of the catalog for the exhibition VANITAS in the GALERíA ARTIFICIAL, Madrid 2008.

Author: Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego

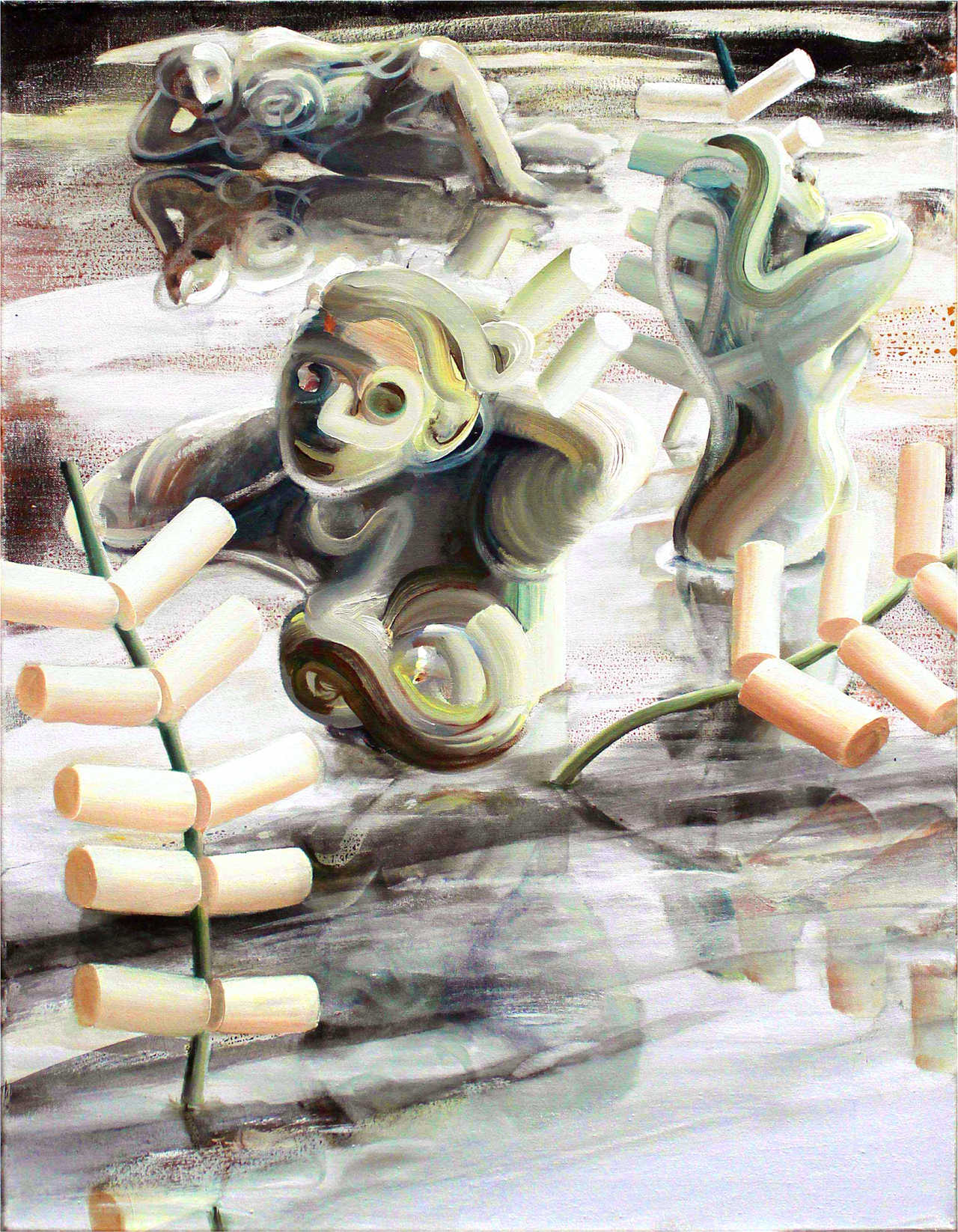

Phantasmagorias and penitences of Rut Massó

One of the classic ways that painting has modulated the tragic has been the genre of vanitas. This is the staging of a kind of melancholic humour that takes possession of the representation, slowly undermining the objects and bodies present in it, unfolding before our eyes the kingdom of fatal temporality and, in the final instance, death itself, but also the inhospitable and implacable corrosion of disappointment and generalised loss and disillusionment. Certainly, Rut Massó’s reading of the genre highlights -not without sarcasm- this brazen dramaturgy where the skull, for example, constitutes the paradigm of agony and the shift to a beyond of the corporeal or the earthy, and where the forest and the night seem to determine a figurative – and furtive – space charged with torment, absurdity, oblivion and terribilità. These are figures that with supreme eloquence express that dimension of the fall of the human gender into solitude, oblivion and schism. As if the characters that appear in Rut Massó’s paintings now find themselves in a lasting distancing from salvation, serenity or, simply, light and tranquillity that could not be worse. Watchful portraits: here there is truly a martyrial tension of the bodies, as if we were looking at “purgative souls“ or, better still, bodies that become only the place where a strength, a ferocious energy, is unleashed that will finally consume them, make them explode, or, in the end, annihilate them. Brazen theatre -as in the horror tales whispered in childhood- in which that pathos of anxiety, desolation, hysteria and negativity is realised. These ill-adjusted, dislocated, hallucinating characters are submerged in a whirlwind of night and devastation, a terrible spirit -we would say- that surpasses them, precisely through the power it puts into torturing and grinding their physiology and body-language, the body itself and the look that maintains them, while it denies all the ties that link them to their daytime and mundane present.

This collection of dramatic and dark gestures and testimonies perhaps also makes up the meaning of an era, as if giving expressive body and form to a historical time, our own, which has produced the great caesura, the breakdown of the perspective of progress, the harsh evidence of the struggle for improbable individual survival – loss, in the end – of any ontological security. Cogito melancolico of a modernity in its final stages that, perhaps, can also echo the unleashings and total apathy of the mannerist and baroque period in which the vanitas, the disconcerted and watchful souls and the fallen angels actually proliferated.

Rut Massó presents us with a particular sacrificial fire, therefore, which functions as a central image of this experience of suffering and that, in the baroque style, also seems to elevate the figure of disillusionment in its nucleus of signification, also bringing about, in this way, the unveiling of the essentially illusory structure in which everything that is human moves. As Clement Rosset suggested in a justly famous text this would be thought that makes the burning and that volatilisation of good which is life into the eloquent emblem of the self-sacrificial urge that strongly dominates it, and that makes it penetrate, precisely because of this, into an undeniable anti-naturalism, into a kind of unreal -almost inverted- dimension of the world in which the frontiers of the irrational, the spectral, the telluric and apocalyptic and the grotesque and maddened come together. In this way, a highly potent nightmarish and turbulent, terminal and strident, intimate and at the same time explosive, imagination is superimposed over any referentiality, offering a melancholic and separated, nocturnal, marginal and extreme world; in the way of a masquerade where this same everyday universe is shown tipped towards unviability and dystopia, as well as the fracture of all the serene meta-accounts: the angelic path, nature, memory, intimacy, the self.

Moreover, it is clear that Rut Massó’s images respond more than anything to a fantastic power. Here, fantasy certainly predominates over any structure of the real or of facts, but this fantastic dimension is not at all liberating, but rather annuls the very presence of a coherent reality while producing an effect of erasure or oblivion over any possibility of the real itself. It is this cancellation of memory and of any locating device and endurance in the world that, at root, painting finally exalts, and it is also this fantastic urge -charged with delirious strength, omens and dark prophecies- that leads the eye or the mind towards these geographies of nocturnal dreams and of loss, with their dark folds, their acid chromatisms and their profound and indomitable corners, there where the immobilising danger and the flame that purges and burns the entrails emerge.

When this strategy is taken to the limit, as in the case of Rut Massó, when it truly addresses an unmaking and transferential urge, then it has its greatest field of action in the pictorial gesture itself, in the strokes and slides of paint itself, that tends to become autonomous or distance itself from any desire for mimesis to begin -as if stretching out and elongating itself in elastic extensions or concentric unfolds of masses of colour- to liquidate all dependence or all exteriority concerning its own system of representation. Then an effective spectralisation of the referents is achieved, while what we could call a perspective of continuous infinitude is introduced, of persistent distancing from any mundanity. What then appears is a succession of stunning visions where reality seems to be crossed or divided by occasional flashes, full of acidity and vitriolic character.

These separated and recondite spaces, these sovereign fictions, require, therefore, a crossing, a phantasmal transit (as real as it is symbolic) that moves passing through melancholia, pain, cruelty and despair, to come to manifest a kind of tragic love for life, a negative furore in which life itself shines and is ignited through all kinds of signs of a denying nature and of a depressing lineage.

Here there is also and without doubt the enigmatic satisfaction that the vanitas offers us. A strange enjoyment that distances itself from the possibility of any beginning of pleasure, to let a cruel entropic energy act: the powerful force of a destruction underlying the objects and bodies of the world that will finally undeniably consolidate that aforementioned death urge which is strongly projected over all the representations. In this sense, Rut Massó’s paintings can well be seen as metaphors or stagings of instability, precariousness and the fragile of the human gender, insofar as it is in the midst of a fatal whirlwind of consumption and potency that devalues us and condemns us to the destiny of corrosion; and when casting off -we would say in baroque style- everything in sad smoke, in shadow, in nothingness. It is, without doubt, exactly this that also comes to emphasise the use of such contrasted and such dark lights and shadows, because they are baroque, in these images. Light that for example filters through the tortured spaces of nature and of the -reduced, asphyxiated- interior spaces. Light that spectralises the faces and strikes the already disconcerted psychic landscape like a burst of madness. Because in Rut Massó there is a clear will to exploit all the effects of light, and particularly the strangest: the chromatic transformations induced by the light of a candle, the decentring of the light source produced by the views against the light or the flashing burst of a low luminous ray in the middle of a dense shadow; the mists, the fires, the shining and the twilights, the turbulent atmospheres and the very violent effects of artificial light, the amplification, in short, of the opposition between shadow and darkness. In the end, what this light reveals with unusual potency is no other than the final and majestic kingdom of an immense shadow, a dark and tenebrous dimension which is perceived or always felt as a voiceless threat, precisely in the middle of which the life of man thrown to the forest and night of the world passes.

The negative pedagogy imposed on us by this painting – not free, as we said, of vitriolic humour, of a bizarre corrosive comicalness – must therefore be seen in terms of its emblematic value. A distorting or dark mirror over the world is placed before us so that in this way an enigmatic morality shines: that which tells us of the denial of the realised or real condition itself of the universe, so that -in a characteristic game of baroque complexity- what is sought, through this very failure of the world to meet up, is to show, as if through nostalgia, the pure and impossible desire for a salving otherness and perhaps the possibility of another redeemed condition that inhabits some place -purely imaginary, possibly- perhaps prohibited to all sensitive experience; offered, therefore, only to desire, to nostalgia of the has-not-been and the will-not-be, to dream and to the promise of a supremely far off redemption. So far off that even the angels themselves seem to be outside this para-reality of salvation, in view of the common destiny of destruction and smoke shared with humans. Because, in short, this threat of devastation and ruin that besieges and depresses the universe of mortals even bears down on angelic reality, which in Rut Massó’s scenes is always shown devoted to liberating itself of its superior condition and merging with the sad ill-fated destiny of the low and fleeting existence of men who, for their part, live the transferred existence in the form of a phantasmal body, an almost teratological disarticulated organism formed by the accumulation of already autonomous parts rather than any overall unity. The achievement for them is shown as difficult, because of the purgative effort, of a life finally prepared to free itself, albeit ideally. In any case, that scene always seems so furtive and future that, significantly, we will never contemplate it.

Therefore, this kind of scratched and confused mirror that Rut Massó offers us would be shown as ambiguously brazen, in that it points, on the one hand, to an irremediable dispersion and expiration and, on the other, towards an (im)possible salvation manifested as inaccessible in the scene. So the essential allegory that all of this seems to transmit would be no other than that of a progressive and radical distancing of the world and the social and cultural nature of men, there where the landscape motif of the nocturnal forest, for example, would function as a eremitic place that would mark the longing for rupture with the world itself. As if, by progressing in the final truth of things, the being-for-death as a destiny, the truth of a dissociated body, without additions or protection, without pomp, cover or control, would surface with the smiling and sarcastic obscenity of the skull. In this sense, the evocation that it -the skull- makes of death proves the contingency of private lives precipitated in the anonymous, banal scene, without biography, of the skinless cranium, the baroque emblem of the disenchantment of the world. Its very bareness annuls the possibility of a human history understood as progress, to the very extent to which the vacant expression of the skull directs its meaning at the mournful and lugubrious melancholic fascination of a nothingness as a paralysing foundation or beginning. In this way, the skull means the imaginary evocation of a profound constitutive vacuum and even more: of an atrocious and impious undressing of the self, also of a stripping of power of a body that must take its leave of its own flesh. Its bony shine and its vacant semantic centre illuminate with lugubrious asceticism make the pictorial scene itself shine with nihilistic strength, devoted now, in this gloominess, to a tragic and penitential reading of the world. This then is a polyphony of the imaginary where a group of moving or unstable figures is always presented, from which comes the predomination of the images of fire and the motifs of errancy, of fall and of movement, as well as the presence of pictorial textures in which the images are stressed as agitation. A watchful group or body, a real body-candle, body-altar-candle of a penitent, a body in constant wakefulness and endlessly purging itself of someone aware of being besieged by the disillusionment and disturbance of the world, entirely possessed by a corrosive and active perplexity and disappointment, submerged in a sick atmosphere of strangeness, traumatic dreaminess and, perhaps, dementia. Body-candle in the middle of the night, destruction, chaos and nothingness; it really seems like the last being using up its meaning in the middle of an exorbitant, disastrous and grotesque universe, which it does not manage to understand, and in which it experiences with delirious consciousness its absolute precariousness and helplessness. An aberrant and unintelligible universe where the objects and the landscapes bow and become malformed and the bodies are consumed, burn and fall as if without remedy, as if in the midst of a dream or a hypertrophied and horrendous nocturnal fantasy, equally as weighed down with omens and ill-fated disorder as it is unpredictable and neutral of all morality. The world itself then becomes spectral and seized by panic, an object of corrupt imagination where any orientation becomes impossible, so that now all that is possible is a taciturn roving and a wandering through the defenceless night, desolation and oblivion with the help of a minimum light, a candle of interiority or cloistered and besieged intimacy, prey to a melancholic stupor that gives in to the rumination of a tortured interiorisation amidst ctonic and undone landscapes. Here the body-candle, tending to be catatonic, must be associated, then, with that of an atrociously corralled and disturbed clairvoyant, a perplexed organism subjected to a depressive and atrocious pressure that turns itself into a pure burning, an extremely intense igneous shock that makes of its eyes the bright testimonies and embers of an undoubtedly apocalyptical prophet. Indeed, this is the man who among all has seen the ominous nothingness of the world, the unfounding of everything, the absurdity as totality, and places it all on an annihilated margin, on the outskirts of any project, in the places of extinction, as if on the threshold, we would say, negatively, of any transcendent, metaphysical perspective. Such tension on the edge of the unbearable is what provokes the implosion itself of this body, the exemplary burst, the irremediable fire as the problematic and cathartic place where all the disorder is crossed and purified. Because doubt and omens, the nihilising conviction and disillusionment destructively persist in it; in what, in essence, is shown as a spirit both resistant in the midst of ambiguity but in a decidedly neurotic torturing condition, as if confirming the painful idea that real life is absent, that we will never belong to ourselves, that we are not our own. These watchful bodies offer us, in the end, a vision which is implosive and in some way closed to the possibility of redemption. Through them is expressed, then, the hard exemplariness of post-utopian, even post-historical, thought. As puppets, or marionettes, of other more powerful forces which degrade, burn and manipulate them, they become the lucid and perplexed testimony of a history that has revealed its most demonic face. They are, like the angels, perennial inhabitants of a fallen universe, of a faltering world and a phantasmagoria in which the subject loses the thread that keeps it united with the existence of things.

However, in the phantasmagorical painting of Rut Massó, the unstoppable and shameless evidence of this disconcerted world ends up tingeing all her scenes with grotesque -and to a large extent comical- unrealism. It happens as if the artist reacts in some way surprised or amazed at the terrible expiration and evanescence of the real, and then there is no other solution than to liberate a kind of response mechanism that suspends trust in some meaning of life, in order to then draw maddened and enigmatic signs, interrogations that are close to trauma and absurdity and that come to reduce and minimise the very weight or importance of the world. So that the extreme evidence of pain and expiration, instead of being transformed into tears, is released in sarcastic witticism, in true tragic laughter. Because in the brazen theatre that Rut Massó puts before us, laughter and comicalness are profoundly penetrated by tragic knowledge. The annihilating capacity of laughter itself helps to soften a pathetic feeling that not only leaves open the possibility of a reading of the world in its tragicomic dimension, but also allows us to conceal laughter itself in triumphant pain; and pain in a sovereign and cruelly tragic happiness.

Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego

Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego ES

Texto del catálogo de la exposición VANITAS en la GALERíA ARTIFICIAL, Madrid 2008.

Autor: Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego

Fantasmagorías y penitencias de Rut Massó

Una de las formas clásicas en que la pintura ha modulado lo trágico ha sido el género de la „vanitas“. Se trata de la puesta en escena de una suerte de humor melancólico que se adueña de la representación, socavando lentamente los objetos y cuerpos en ella presentes, desplegando ante nuestros ojos el reino de la temporalidad fatal y, en última instancia, la muerte misma, pero también la corrosión inhóspita e irreductible del desengaño, la pérdida y la desilusión generalizadas. Ciertamente, la lectura que Rut Massó realiza del género resalta -no sin sarcasmo- esta dramaturgia desgarrada donde la calavera, por ejemplo, constituye el paradigma de la agonía y el traslado a un más allá de lo corporal o lo terreno, y donde el bosque y la noche parecen determinar un espacio figurativo -y furtivo- cargado de tormento, de sinsentido, olvido y terribilitá. Estamos antes figuras que expresan con toda elocuencia esa dimensión de la caída del género humano en la soledad, el olvido y la esquizia. Como si los personajes que en los cuadros de Rut Massó aparecen se hallasen ya en un duradero e impeorable alejamiento de la salvación, la serenidad o, simplemente, la luz y el sosiego. Retratos en vela: he ahí, verdaderamente, una tensión martirial de los cuerpos, como si estuviésemos ante “almas purgantes” o, mejor aún, cuerpos que se tornan tan sólo el lugar donde se desencadena una fuerza, una energía feroz que acabará por consumirlos, por hacerlos estallar, o, en fin, por aniquilarlos. Teatro desgarrado -como en los relatos de terror o los cuentos terribles que se susurran en la infancia- en que se cumple ese pathos de angustia, desolación, histeria y negatividad. Estos personajes desajustados, dislocados, alucinados, se ven sumergidos en un remolino de noche y devastación, un espíritu -decíamos- terrible, que los excede, precisamente por la fuerza que pone en torturar y triturar su fisiología y su gestualidad, el mismo cuerpo y la mirada que los mantiene, mientras va negando todos los lazos que los vinculan a su presente diurno o mundano.

Esta colección de gestos y testimonios dramáticos y oscuros acaso componga, también, el sentido de una época, como dando cuerpo y campo expresivo a un tiempo histórico, el nuestro, donde se ha producido la gran cesura, la quiebra de la perspectiva de progreso, la dura evidencia de la lucha por la improbable supervivencia individual, la pérdida, en fin, de cualquier seguridad ontológica. Cogito melancólico de una modernidad en sus postrimerías que, acaso también, pueda rimar con los desenfrenos y abulias del periodo manierista y barroco en que las vanitas, las almas desconcertadas y en vigilia y los ángeles caídos, precisamente, proliferaron.

Nos presenta Rut Massó un particular incendio sacrificial, entonces, que funciona como imagen central de esa vivencia del sufrimiento y que, al modo barroco, parece elevar también en su núcleo de significación la figura del desengaño; propiciando, de este modo, el desvelamiento también de la estructura esencialmente ilusoria en que se mueve todo lo que es humano. Como ya sugirió en un escrito justamente célebre Clement Rosset , estaríamos ante un pensamiento que hace de la quema y de la volatilización del bien que es la vida el emblema elocuente de la pulsión autosacrificial que la domina con fuerza, y que la hace penetrar, precisamente por ello, en un innegable anti-naturalismo, en una suerte de dimensión irreal -casi invertida- de mundo en que las fronteras de lo irracional, lo espectral, lo telúrico y apocalíptico y lo grotesco y enloquecido se dan la mano. De esta manera, un muy potente imaginario pesadillesco y turbio, terminal y estridente, íntimo y al tiempo explosivo, se superpone por encima de cualquier referencialidad, ofreciendo un mundo melancólico y separado, noctámbulo, marginal y extremo; al modo de una mascarada en donde se muestra este mismo universo cotidiano volcado hacia la inviabilidad y la distopía, así como la fractura de todos los metarrelatos serenos: la vía angélica, la naturaleza, la memoria, la intimidad, el yo.

Es evidente, además, que las imágenes de Rut Massó responden antes que nada a una potencia fantástica. Aquí la fantasía, ciertamente, prima sobre cualquier estructura de lo real o de los hechos, pero esta dimensión fantástica no es en absoluto liberadora, sino que más bien anula la presencia misma de una realidad coherente, y viene, asimismo, a realizar como un efecto de borrado o de olvido sobre cualquier posibilidad de real mismo. Es esta anulación de la memoria y de cualquier dispositivo de ubicación y perduración en el mundo lo que, en el fondo, la pintura acaba por exaltar, y es también esta pulsión fantástica -cargada de fuerza delirante, de presagios y profecías sombrías- la que conduce el ojo o la mente hacia esas geografías de ensueño nocturno y de pérdida, con sus pliegues tenebrosos, sus ácidos cromatismos y sus rincones profundos e indómitos, allí donde aflora el peligro inmovilizador y la llama que purga y quema las entrañas. Cuando esta estrategia se lleva al límite, como es el caso de Rut Massó, cuando se ocupa verdaderamente en una pulsión desrealizadora y transferencial, entonces tiene su mayor campo de acción en el gesto pictórico mismo, en los trazos y los deslizamientos de la propia pintura, que tiende a autonomizarse o a alejarse de cualquier voluntad de mímesis para empezar -como estirándose y alargándose en extensiones elásticas o despliegues concéntricos de masas de color- a liquidar toda dependencia o toda exterioridad respecto a su propio sistema de representación, y entonces se alcanza una efectiva espectralización de los referentes, al tiempo que se introduce lo que podríamos llamar una perspectiva de continua infinitud, de pertinaz alejamiento de cualquier mundanidad. Lo que aparece entonces es una sucesión de visiones fulgurantes donde la realidad es como atravesada o hendida por rayos ocasionales, plenos de acidez y carácter vitriólico. Estos espacios apartados y recónditos, estas soberanas ficciones, requieren, pues, de una travesía, un fantasmal tránsito (tan real como simbólico) que se desplaza cruzando la melancolía, el dolor, la crueldad y el desespero, para llegar a manifestar una suerte de amor trágico por la vida, furor negativo en que la vida misma brilla y se incendia a través de todo tipo de signos de trazo negador y de estirpe depresora.

He aquí, también y sin duda, la enigmática satisfacción que nos ofrecen las vanitas. Un extraño goce que se aleja de la posibilidad de cualquier principio de placer, para dejar actuar una cruel energía entrópica: la fuerza poderosa de una destrucción subyacente a los objetos y cuerpos del mundo que acabará por consolidar innegablemente esa aludida pulsión de muerte que se proyecta muy fuertemente sobre todas las representaciones. En este sentido, los cuadros de Rut Massó bien pueden verse como metáforas o escenificaciones de la inestabilidad, la precariedad y lo frágil del género humano, en la medida en que éste se halla en medio de un torbellino fatal de consumición y potencia que nos desbarata y condena al destino de la corrosión. Y al deshacerse -diríamos a lo barroco- de todo en triste humo, en sombra, en nada. Es esto mismo, sin duda, lo que también viene a enfatizar el uso de las luces y las sombras tan contrastadas, tan tenebristas, por barrocas, en estas imágenes. Luz que por ejemplo se filtra a través de los espacios torturados de la naturaleza o de los -reducidos, asfixiados- espacios interiores. Luz que espectraliza los rostros y golpea como un estallido de locura el paisaje psíquico ya de por sí desconcertado. Porque en Rut Massó se da una clara voluntad de explotar todos los efectos de la luz, y particularmente los más extraños: las transformaciones cromáticas inducidas por la luz de una candela, los descentramientos de la fuente luminosa que producen los contraluces o el estallido relampagueante de un rayo luminoso rasante en medio de una sombra espesa; las brumas, los incendios, los resplandores y los crepúsculos, las atmósferas turbias y los efectos muy violentos de luz artificial, la amplificación, en fin, de la oposición entre sombra y tinieblas. A fin de cuentas, lo que esta luz revela con potencia inusitada no es otra cosa que el reinado final y mayestático de una inmensa sombra, una dimensión oscura y tenebrosa que se percibe o se siente siempre al modo de una sorda amenaza, aquélla precisamente en medio de la cual transcurre la vida del hombre arrojado al bosque y la noche del mundo.

La pedagogía negativa que nos impone esta pintura -no exenta, como dijimos, de humor vitriólico, de una bizarra comicidad corrosiva- debe verse, por tanto, en su valor emblemático. Se nos coloca un espejo deformante u oscuro sobre el mundo para que de este modo brille una enigmática moralidad: la que nos cuenta de la desautorización de la propia condición realizada o fáctica del universo, de modo que -en un característico juego de complejidad barroca- se piensa, a través de este mismo desencuentro del mundo, mostrar como por nostalgia el deseo puro e imposible de una otredad salvífica y tal vez la posibilidad de una otra condición redimida que habita en algún lugar -puramente imaginario, posiblemente- prohibido acaso a toda experiencia sensible; ofrecida por lo tanto solamente al deseo, a la nostalgia de lo no-sido y de lo que no-será, al sueño y a la promesa de una redención sumamente lejana. Tan alejada que hasta los ángeles mismos parecen hallarse ajenos a esta para-realidad de salvación, a la vista del común destino de destrucción y humo que comparten con los humanos. Porque, en definitiva, esta amenaza de devastación y ruina que asedia y deprime el universo de los mortales está gravitando incluso sobre la realidad angélica, que en las escenas de Rut Massó siempre se muestra entregada a liberarse de su condición superior y a fundirse con el triste destino aciago de la existencia baja y caduca de los hombres, aquéllos que, por su parte, viven la existencia transferida en la forma de un cuerpo fantasmal, un organismo casi teratológico y en desarticulación conformado más bien por la acumulación de partes ya autónomas que por cualquier unidad de conjunto. Difícil se muestra, para ellos, la consecución, por el esfuerzo purgativo, de una vida dispuesta por fin a liberarse, aunque sea idealmente. En todo caso esa escena semeja siempre tan furtiva y futura que, significativamente, nunca la contemplaremos.

De modo que esta suerte de espejo arañado y confuso que nos ofrece Rut Massó se mostraría anfibológicamente desgarrado, en cuanto apunta, por un lado, a una dispersión y caducidad irremediable, y por otro hacia una salvación (im)posible que se manifiesta como inaccesible en la escena. Con lo que la alegoría esencial que todo ello semeja transmitir no sería otra que la de un progresivo y radical distanciamiento del mundo y la naturaleza social y cultural de los hombres, allí donde el motivo paisajístico del bosque nocturno, por ejemplo, funcionaría como un lugar eremítico que marcaría el anhelo de ruptura con el propio mundo. Como si, a fuerza de progresar en la verdad última de las cosas, ese su ser-para-la-muerte como destino, aflorase, con la obscenidad risueña y sarcástica de la calavera, la verdad de un cuerpo disociado, sin añadidos ni abrigos, sin galas, coberturas ni dominio. En este sentido, la evocación que ella -la calavera- realiza de la muerte, evidencia la contingencia de las vidas particulares, precipitadas en la escena anónima, banal y sin biografía del cráneo pelado, emblema barroco del desencantamiento del mundo. Su misma desnudez anula la posibilidad de una historia humana entendida como progreso, en la medida misma en que la mirada vacía de la calavera dirige su sentido a la melancólica fascinación lúgubre y luctuosa de una nada como fundamento o principio paralizante . De este modo, la calavera supone la evocación imaginaria de un profundo vacío constitutivo, y aún más: de un desnudamiento atroz e impío del yo, también de una despotenciación de un cuerpo que ha de despedirse de su propia carne. Su brillo óseo y su centro semántico vacío iluminan de lúgubre ascetismo, hacen que fulgure con fuerza nihilista la propia escena pictórica, entregada ahora, en este su tenebrismo, a una lectura trágica y penitencial del mundo. Estamos, pues, ante una polifonía de lo imaginario donde se presenta siempre un conjunto de figuras móviles o inestables, de ahí el predominio de las imágenes del fuego y los motivos de errancia, de caída o de movimiento, así como la presencia de unas texturas pictóricas en que las imágenes se potencian como agitación. Grupo o cuerpo en vela, en verdad cuerpo-vela, cuerpo-cirio de penitente, cuerpo en vigilia constante y en purga sin pausa de quien se sabe asediado por la desilusión y la turbación del mundo, enteramente poseído por una perplejidad y un desengaño corrosivos y activos, sumido en una atmósfera enferma de extrañeza, onirismo traumático y, acaso, demencia. Cuerpo-vela en medio de la noche, la destrucción, el caos y la nada; bien parece el último ser gastando su sentido en medio de un universo desorbitado, desastroso y grotesco, que no alcanza a entender, y en el que vive con conciencia delirada su absoluta precariedad y desamparo. Universo aberrante e ininteligible donde los objetos y los paisajes se curvan y malforman y los cuerpos se consumen, arden y caen como sin remedio, como en medio de un sueño o una fantasía nocturna hipertrofiada y horrenda, tan cargada de auspicios y desórdenes aciagos como imprevisible y neutra de toda moralidad. El mundo entonces se vuelve él mismo un todo espectral y pánico, un objeto de una imaginación corrupta donde toda orientación se vuelve imposible, de modo que ahora ya tan sólo cabe un errar taciturno y un vagabundear por la noche desamparada, la desolación y el olvido con la ayuda de una mínima luz, una candela de la interioridad o la intimidad clausurada y asediada, presa del estupor melancólico que se entrega a la rumia de una interiorización torturada en medio de paisajes ctónicos y deshechos. Aquí el cuerpo-vela, tendencialmente catatónico, ha de asociarse, pues, con el de un vidente atrozmente acorralado y turbado, organismo perplejo sometido a una presión depresiva y atroz que vuelve su mirada una pura quemazón, una intensísima conmoción ígnea que hace de esos sus ojos los testimonios y rescoldos fulgurantes de un profeta de registro indudablemente apocalíptico. Ciertamente, éste es el hombre que entre todos ha visto la nada ominosa del mundo, la desfundamentación de todo, el sinsentido como totalidad, y todo ello lo coloca, precisamente, en un margen aniquilado, en las afueras de cualquier proyecto, en los lugares de la extinción, como ante el umbral, diríamos, en negativo, de cualquier perspectiva trascendente, metafísica. Tal tensión al borde de lo insoportable es lo que provoca la implosión misma de ese cuerpo, el estallido ejemplar, el incendio irremediable como lugar problemático y catártico donde se cruzan y purifican todos los desórdenes. Porque la duda y los presagios, la convicción nihilizadora y el desengaño persisten en él destructivamente; en él que, por esencia, se muestra como espíritu al tiempo resistente en medio de la ambigüedad pero bajo una condición decididamente neurótica, torturante, como confirmando la idea dolorosa de que la verdadera vida está ausente, de que nunca nos perteneceremos a nosotros mismos, de que no somos nuestros. Estos cuerpos en vela nos ofrecen, en fin, una visión implosiva y en cierto modo cerrada a la posibilidad de una redención. A través de ellos se expresa, entonces, la dura ejemplaridad de un pensamiento postutópico, incluso posthistórico. Títeres como son, o marionetas, de otras fuerzas más potentes que los degradan, incendian y manipulan, se convierten en el lúcido y perplejo testimonio de una historia que ha revelado su rostro más demoniaco. Ellos son, como los ángeles, habitantes perennes de un universo caído, de un mundo en falta y una fantasmagoría en la cual el sujeto pierde el hilo que lo mantiene unido a la existencia de las cosas.

Sólo que, en la pintura fantasmagórica de Rut Massó, la evidencia imparable e impúdica de este mundo desconcertado acaba por teñir de irrealismo grotesco -y en buena medida cómico -todas sus escenas. Sucede como si la artista reaccionase en cierta forma sorprendida o asombrada ante la terrible caducidad y evanescencia de lo real, y entonces no quedase otra solución que liberar una suerte de mecanismo de respuesta que suspende la confianza en algún sentido de la vida, para trazar entonces signos enloquecidos y enigmáticos, interrogaciones que bordean el trauma y el sinsentido y que vienen a reducir y minimizar el propio peso o la importancia del mundo. De forma que la extrema evidencia del dolor y la caducidad, en lugar de resolverse en llanto, se libera en sarcástica humorada, en verdadera risa trágica. Porque en el teatro desgarrado que nos propone Rut Massó la risa y la comicidad están profundamente penetradas de saber trágico. La capacidad aniquilante de la risa misma colabora entonces a suavizar un sentimiento patético que no sólo deja abierta la posibilidad de lectura del mundo bajo su dimensión tragicómica, sino que permite ocultar la risa misma en el dolor triunfante y el dolor en una soberana y cruel alegría trágica.

Alberto Ruiz de Samaniego

| 2024 | “PANGÄA”, offspace Milchstrasse 4, Munich, Germany. |

| 2022/23 | “ON THE ROCKS”, P38 Munich, Germany. |

| 2019 | “Blaue Stunde / Hora Azul”, SVT Espacio de Arte, Vigo, Spain. |

| 2019 | “RETROVISOR”, Artothek, Munich, Germany. (catalog) |

| 2017 | “13,6 Milliarden Jahre Danach”, CAS, Munich, Germany. (catalog) |

| 2014 | “LAGOAS”, Knust x Kunz+, Munich, Germany. |

| 2013 | “Waldmetall”, Galería Lilliput, Vigo, Spain. |

| 2009 | “Romántica Sinapsis”, Galería Sargadelos, A Coruña and Santiago, Spain. |

| 2008 | “Vanitas”, Galería Artificial, Madrid, Spain. (catalog) |

| 2007 | “Vanitas”, Die Aenderei, Munich, Germany. |

| 2007 | Galería Anexo, Pontevedra, Spain. |

| 2003 | “Sentinas-Kielräume”, Galerie Goethe 53, Munich, Germany. |

| 1997 | Galería Abel Lepina, Vigo, Spain. |

| 1995 | “Habitación 25”, videostallation, Sala Galán, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. |

| 1995 | Galería Sargadelos, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. |

| 2024 | PODER INTERIOR, Galería Luisa Pita, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Artists: Menchu Lamas, Rut Massó, Ana Margarita Ramírez. |

| 2023 | GLÜCK OHNE ENDE, PING RODACH contemporary, Munich, Germany. __ EDEN, Munich, Germany. Curated by Judith Grassl. __ GESOTTEN, Galerie FOE, Munich, __ FLORA UND FAUNA, offspace P38, Munich, Germany. Curated by Rut Massó and Analía Martínez. |

| 2022 | ENTWEDER JETZT ODER SPÄTER, Kösk Munich, Germany. Curated by Emanuel Wadé and Sebastian Mayrhofer. __ ALLES FÜR ALLE, OpenQ artspace, Munich, Germany. Curated by Florian Haller. __ ON THE ROAD, offspace P38, Munich, Germany. Curated by Rut Massó and Annabelle Mehraein. |

| 2021 | NURTRING UNCERTAINTIES, CGAC Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Curated by Ángel Cerviño. __ FAST FORWARD >>, Fürstenstr. 11, Munich, Germany. Curated by Analía Matínez. __ LUZ! BLAU, ROT E CAPELLI GRASSI, Galerie Lake, Oldenburg, Germany. Curated by Endy Hupperich. __ FOR FREE* (*artists are not working for free), a solidary exhibition with over 100 Artists, Galerie Andreas Binder, Munich, Germany. Curated by Daniel Man. __ WIE IN ECHT, offspace XXXVIII, Munich, Germany. |

| 2020 | SCHANZENTISCH, Offspace XXXVIII Munich, Germany. __ WALDEN, Kulturzentrum Giesinger Bahnhof, Munich, |

| 2019 | JAHRESGABEN, Kunstverein Munich, Germany. |

| 2018 | TOY BITCHES FUCK YOU, Galerie Kai Erdmann, Hamburg. |

| 2015–16 | DIPLOMATIC BAG, Madrid, Santiago de Chile, Rom, New York, Melbourne. Curated by Nilo Casares. __ WURMLOCH, Rathausgalerie Munich, Germany. |

| 2013-14 | WORLD SKETCH, Museum MARCO Vigo, Spain. Curated by Ángel Cerviño and Alberto González Alegre. |

Contact

info@rutmasso.com

+49-(0)163 487 9193

Studio:

Pfeuferstr. 38, Atelier 4

D-81373 Munich

Impressum

Rut Massó, Pfeuferstr. 38, Atelier 4 , D-81373 Munich, Germany

+49-(0)163 487 9193

E-mail: info@rutmasso.com

Internet: www.rutmasso.com

USt-Identifikationsnummer gemäß § 27 a Umsatzsteuergesetz

Haftungshinweis: Trotz sorgfältiger inhaltlicher Kontrolle übernehmen wir keine Haftung für die Inhalte externer Links. Für den Inhalt der verlinkten Seiten sind ausschließlich deren Betreiber verantwortlich.

Urheberrecht: Die Inhalte und Werke auf diesen Seiten unterliegen dem deutschen Urheberrecht. Die Vervielfältigung, Bearbeitung, Verbreitung und jede Art der Verwertung außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechtes bedürfen der schriftlichen Zustimmung des Autors.

Grafik: Carina Müller _ Programmierung: Markus Buhl

© alle Abbildungen: Rut Massó, Siegfried Wameser

- Current

- Vita

- Text

- Solo Exhibitions

- Group Exhibitions

- Contact & Impressum